‘A date which will live in infamy’

Published 5:10 am Wednesday, December 7, 2016

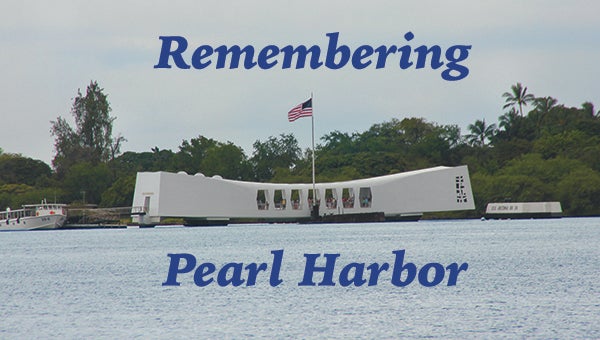

Pictured is a memorial set at the site of the sinking of the USS Arizona at Pearl Harbor. This year marks the 75th anniversary of that fateful day in which more than 2,000 Americans lost their lives.

Seventy five years ago, on Dec. 7, 1941, an event called “a day in infamy” by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, changed the world and many lives forever. On that date, a swarm of 360 Japanese warplanes bearing the sign of the red sun appeared flying low over Pearl Harbor, located on the island of Oahu in Hawaii. After two hours of bombing, the planes flew away and left the harbor, the home of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, in shambles and more than 2,000 people dead.

The next day President Roosevelt went before Congress and declared war on Japan. This event propelled the U.S. into a four-year long struggle that affected many, including those who live in Brewton.

One person from Brewton that saw the attack first hand was the late Richard Hesler, and on the occasion of the 60th anniversary, he took the time to be interviewed. The following is his account of that day that he remembered as if it happened yesterday.

“I was on the signal bridge of the cruiser, USS Raleigh just before 8 a.m.,” he said. “I was waiting for the flagship USS Pennsylvania to run up the flag at 0800 hours so I could tell the striker to raise the flag on the Raleigh.

“I watched as a plane came in low over the palm trees, but that was not unusual.” he added. “I did think it was a bit odd for them to be making practice runs on a Sunday morning. Then I saw something fall from the plane, but that was not so unusual either. They often dropped flour sacks on their practice runs. I was talking with one of my shipmates about the plane when all of a sudden, I heard an explosion and then I saw the side of the plane as it pulled out of a dive. I saw the red sun painted on the side and I knew then that it was not one of ours and that the bombing was real.

“Then I heard more and more explosions, from different places and saw plane after plane coming over us,” he added. “They would fly low over the palms, drop their torpedos and then climb out of their dive. We stood by helplessly as they flew toward the line of cruisers that was lined up.”

The cruisers could do little with their small six-inch guns and men were running everywhere. According to Hesler, the ship’s captain was running around in his pajamas and wearing a steel helmet, but he could do little to help the situation.

The explosions ruptured Hesler’s eardrum. He said that the attack seemed as if it was endless.

The Japanese thought the carriers were in the harbor but were surprised to find that the cruisers were moored in their place.

“For the next two hours they pounded us with torpedos,” Hesler said. “Two of the torpedos were dropped on the USS Utah, which was moored next to the Raleigh, and then flipped upside down. We were struck with one torpedo near the number one engine room and another that went through three decks and exploded below the ship, which began to list to the side. We were ordered to throw everything we could overboard so the ship wouldn’t turn over. We threw everything we could overboard. We threw the heavy stuff first but eventually, even the mops and pails were tossed over the side. To make matters worse, after the bomb hit us we were dead in the water but at that time no one had been killed on the Raleigh, The bombing came in two waves and it seemed as if they were getting bigger every time they flew over.”

The USS Raleigh was credited with shooting down three of the enemy planes and they finally got underway to try to leave the harbor. It was decided to beach the ship because they were afraid they would block the entrance to the harbor. The crew was given bare necessities and later allowed to go down into the ship.

“There was oil everywhere,” Hesler said. “We were given postcards by the Navy to let our folks know we were still alive. I have to confess, I didn’t send mine right away.”

Hesler was just a young man of 22 when he joined the U.S. Navy in 1938. Due to the war, he re-enlisted, staying another four years.

In 2001, when he sat and told of his experiences on that day, he was still collecting anything he could read about Pearl Harbor and even had a small office which held his many remembrances. It was always evident that he retained a real interest in that long-ago-day in Hawaii. Today, there are many who stand at the USS Arizona Memorial and look down at the remains of the Arizona, and the tomb of more than 1,000 crew members who died on that day seventy-five years ago.

He did say that he wondered if anything could have been done to prevent it. He also wondered about the breakdown of communications between Pearl to the mainland.

“It was certainly a victory for the Japanese,” he said. “I don’t think one could refer to it as a victory. We were ambushed and were like sitting ducks. If we had even a warning, we would have been ready.”

Another item of interest was the effect on another Brewton citizen, Broox Garrett Sr. Garrett, who was in the Navy Reserve, received orders on Monday, Dec. 8, to report for duty immediately. He was connected to the intelligence section of the Navy. Broox Garrett Jr. said that his father always said that he was the first one to be ordered to active duty in this area.